From nurturer and warrior to teacher, healer and muse, Armenian women have passed down to each generation an ideal of what womanhood looks like. Historically, in a patriarchal society, these definitions are, unsurprisingly, perpetuated by the sensibilities of male artists and writers. Yet this does not necessarily mean that the characters of their focus are weak, inferior or subordinate. Here we explore some noteworthy examples of celebrated 20th and 21st century works in which the central figures are Armenian women—in all their fascinating complexities, contradictions, exaltations, and symbolic representations.

Peter Balakian

Poet and Colgate University Professor of English Peter Balakian comes from a family of particularly strong and brilliant women. His aunt Nona Balakian was a literary critic and editor at the New York Times Sunday Book Review for over forty-three years, while her sister Anna Balakian was an esteemed literary critic and professor at New York University. Both may have inherited their intelligence and inner strength from Balakian’s grandmother Nafina, whom we meet in his bestselling 1997 memoir Black Dog of Fate. A woman marked forever by the events of 1915, she passes down sometimes traumatic family history and traditions to her grandchildren. Nafina serves as a link to the past and a bridge between seemingly parallel but incompatible universes: the serene suburban Bergen County, New Jersey of the late 1970s and the turbulent old country of Armenia circa 1915.

Balakian writes: “When I was with my grandmother, I had access to some other world, some evocative place of dark and light, some place that ran like an invisible force from this country called Armenia to New Jersey. It was something ancient, something connected to earth and words, and blood and sky.” His grandmother interprets dreams, believes in superstitions, and teaches him the old ways: “My grandmother liked to tell all of us her dreams, but it was to me, when we were alone, that she told her stories. Perhaps she had told the same ones to her daughters, when they were young although no one ever mentioned them.” Here as in other places, the survivors are motivated by an almost superhuman will to survive. Peter Balakian’s memoir pays tribute to his grandmother’s strength: Nafina goes so far as to take on the international legal system to seek justice for her family’s stolen property. She shows the young Peter a deed from the old country, and a legal document that she had a lawyer draft in the hopes of recovering what has been lost from the Turkish government. Nafina is both morally strong and remarkably intelligent as well: she is willing to start a legal battle in a country no longer hers, from an adoptive one, in a language that she has had to learn from scratch as an adult. The reader can only marvel at such inner fortitude.

“Armenians pride themselves on being the first Christian nation and attribute that historical fact to Gregory the Illuminator or King Tiridates the Great. They often forget that the king’s sister, Princess Khosrovidukht, convinced him to release Gregory from the Dungeon of Virap after thirteen years of imprisonment. So, Armenians actually became Christians thanks to a woman.”

Bared Maronian

In his powerful Emmy-nominated documentary The Women of 1915, Bared Maronian introduces viewers to Aurora Mardiganian, a survivor of 1915 sold as a slave before escaping to America where she starred in “The Auction of Souls.” The film helped raise millions of dollars for the Near East Relief Society, an organization that saved thousands of Armenian orphans from certain starvation. However, as Maronian notes, the contributions of Armenian women are too often pushed into the background, one reason for his decision to make his documentary: “Women have always been the unsung heroes of the Armenian reality…Besides being the consummate nurturer in classical terms, the Armenian woman has always been the savior of our nation.”

Maronian has a point, since even in Armenian mythology Nané, besides being the mother goddess, was also the goddess of war and wisdom: “So you see from the beginning of times, the Armenian woman was characterized as a nurturer, a warrior, and a source of knowledge,” says Maronian. “Not just a mom!” He is also quick to point out how women have often willfully been erased from our history, even in the oft-told story of the Armenian 4th century A.D. conversion to Christianity: “Armenians pride themselves on being the first Christian nation and attribute that historical fact to Gregory the Illuminator or King Tiridates the Great. They often forget that the king’s sister, Princess Khosrovidukht, convinced him to release Gregory from the Dungeon of Virap after thirteen years of imprisonment. So, Armenians actually became Christians thanks to a woman.”

Henri Verneuil

Born Ashot Malakian, director Henri Verneuil’s films belong to the annals of French film history. Verneuil was born in 1920 Rodosto, Turkey (present-day Tekirdağ); his family fled to Marseille in order to escape persecution in 1924. He later recounted his childhood experience in the novel Mayrig, which he made into a 1991 film with the same title. Here we learn that his once prominent Armenian family arrived in France with just a few gold coins hidden in a piece of clothing. Yet they had something far more precious—one another. Verneuil’s two aunts and his mother doted on him ceaselessly while also working tirelessly to rebuild their shattered lives. The enterprising Armenian immigrant recurs as a trope in depicting life after genocide.

Whether in Fresno, Worcester or Syracuse in the United States, Paris or Marseille in France—wherever Armenians found refuge, they toiled and labored to reconstitute their decimated communities. His mother and her two sisters actually found piecemeal work in Marseille and even put his father to work sewing buttons on dress shirts, ultimately opening their own shop. The raw emotions of both book and film come straight from a grateful son’s heart.

In describing that feeling of exile that permeated their lives, Verneuil once stated: “In retrospect, I realize that during all those years where we loved each other so much, we never once expressed that love to each other in actual words. Partly out of modesty, partly to avoid, because we feared emphasizing or admitting a harsh reality: that our difficult situation was in fact permanent.” So loving are his two aunts Aya and Kayané, sacrificing so much to give little Ashot/Henri the type of future that the Genocide destroyed for their own generation, it comes as no surprise that Verneuil referred to them as his three mothers. One must also give credit to his father, portrayed in the film by international superstar Omar Sharif. Breaking stereotype, Hagop Zakarian, gave his wife and two sisters-in-law the space and respect to not only run the household but also the family business.

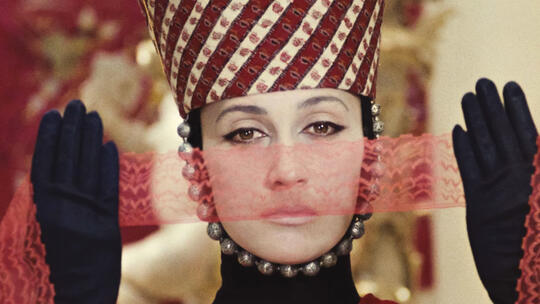

Sergei Parajanov

A modern filmic version of the life and times of the wandering 18th century bard Harutyun Sayatyan, commonly known as Sayat Nova, Sergei Parajanov’s The Color of Pomegranates is widely hailed as one of the most beautiful films of the 20th century. Imprisoned by the Soviet government for being homosexual and/or “deviant,” the Tbilisi-born filmmaker would eventually make films in Ukraine, Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia, where he is buried in the Komitas Pantheon. Parajanov’s muse in The Color of Pomegranates, the Georgian actress Sofiko Chiauruli, plays no less than six roles: these include Sayat Nova as a youth, the poet himself as a youth, the poet’s love interest, a mime, and finally the Angel of Resurrection. These roles mix male and female characters, and all of them appear gender fluid. One of the film’s most famous scenes shows Chiauruli’s torso, with one breast covered with a conch shell.

From that point on, Parajanov uses the shell to represent the breast and female sensuality. The color of pomegranates: a deep, earthy red, comes to represent the red cheeks of his beloved, not blood or nationalism. Hence the woman herself becomes a symbol of peace, and object of sensual desire. As a symbol of fertility and life ever since Assyrian and Mesopotamian times the pomegranate is associated with peace and beauty in the Venusian sense, reflecting the Sayat Nova ballad “Inanna, who loves apples and pomegranates, Has brought forth potency”…“give the fruit to the woman and have her suck the juices. That woman will come to you: you can make love to her.” At another point in the film, the young Sayat Nova peeks through the window of one of the city’s Turkish baths and observes King Erekle II and his sister Ana bathing—and duly falls in love with the future Queen. Parajanov clearly recognizes the beauty and sensual power of women, while celebrating one of our greatest poets and composers—Sayat Nova.

Nafina is both morally strong and remarkably intelligent as well: she is willing to start a legal battle in a country no longer hers, from an adoptive one, in a language that she has had to learn from scratch as an adult. The reader can only marvel at such inner fortitude.

Alexander Dinelaris

Few theatrical plays describe the atrocities that took place during the Armenian Genocide in quite such gory detail. In the 2012 theatrical play Red Dog Howls by Alexander Dinelaris, one must wait until the very end to learn exactly to what heinous act by the Turkish soldiers the protagonist Rose was subjected. Seemingly everyone, from Yale Comparative Literature professor Shoshonna Feldman to Armenian philosopher Marc Nichanian, has theorized of late the role of the victim is also to serve as the eyewitness. But haunted is she from the sordid truth that Rose sees the world through gray colored glasses.

When Michael Kiriakos’s father passes away in Red Dog Howls, he discovers some old letters written to his father by a woman named Rose in Washington Heights. Perplexed, Michael tracks her down, only to find out that she is his grandmother, and that he is, in fact, of Armenian descent. Over Armenian delicacies, the two converse daily and become trusted friends. Rose slowly reveals the family history in the old country and at the end of the play delivers one last anguished monologue in which she utters the vile details of a terrifying encounter with Turkish soldiers, thrusting her psyche into a chasm of despair. Dinelaris delineates her character as the prototypical victim but surviving witness, an Armenian woman gripped by the past yet strong enough to begin anew in a foreign land. The unspeakable crime to which Rose finally gives voice is the cathartic moment that offers us a glimpse of her redemption.

Aris Janigian

In Armenian works, one often finds a tendency to stereotype: men as macho types who go off daily to work and war, while women are portrayed as caregivers and transmitters of culture. One should not be surprised that novelist Aris Janigian offers us the most nuanced counterpoint to the idealized women portrayed above. Janigian notes: “Armenian mothers are generally stereotyped as nurturing, protective, morally virtuous: she who wipes away the tears, settles family problems, leads the kids to church and bakes the choreg—stable matriarchs even within a generally patriarchal culture.” But like their male counterparts, the reality is that not all Armenian women are models of virtue. In his haunting 2003 novel Bloodvine, Janigian spins a tale of love, deceit, and redemption like few others. In this partly biographical story of an Armenian family one generation removed from the Genocide, the fight over a valuable piece of farmland tears a family apart.

Bloodvine offers up different female archetypes beginning with Zabel and her ironically named mother Angel, a genocide survivor who turns her husband against his half brother. According to Janigian, mother and daughter form a kind of primitive blood-bond based in fear, imagined scarcity, and superstition that collides with the male character Andy and his modern ways, “somewhere between Armenian and American.”

While Zabel is fierce and strong, she is anything but nurturing. Janigian juxtaposes her with two other women who come closer to the Armenian ideal portrayed by other filmmakers and writers: “Karen, Andy’s love interest and eventual wife, and especially her mother Valentine, also a genocide survivor, respond differently to the tragic history that they inherited from their ancestors. Valentine approaches life itself as a gift,” Janigian notes, “embracing pleasure and kef, dancing and play, music and laughter as the only answer to her human tragedy.” Valentine puts the past behind her for good, embracing life once again. Her character represents the Armenian woman as a life-affirming force who allows herself to live life to the fullest.

Listen to the moving soundtrack of Women of 1915 which includes an original song called “We Stand” written and produced specifically for the film in addition to five Armenian folk songs performed by women.